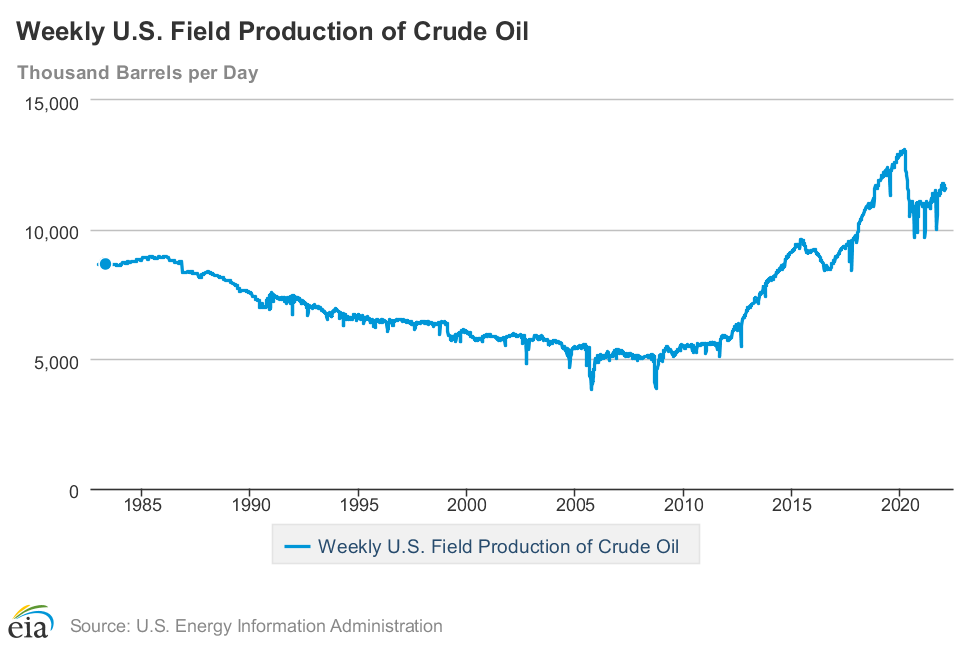

It shows weekly US oil production from the early 1980s through 1/2/2022. Production peaked in March, 2020 and declined through June, 2020. It has been basically constant with a slight increase since then. So much for not producing. OPEC didn’t change their production stance recently. Besides, even if they did, they all cheat on their quotas which is why they can’t keep prices up, except when the US is printing money with abandon.

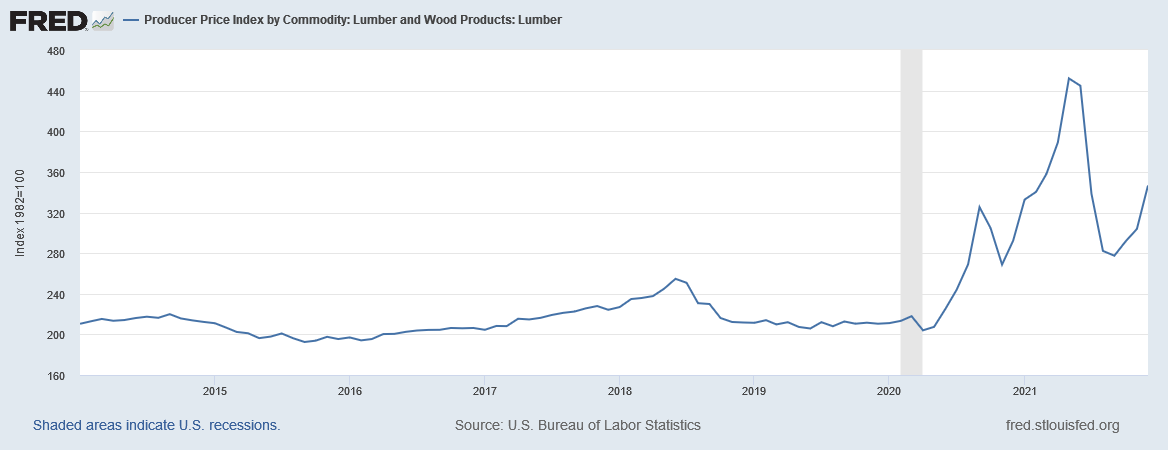

He believes that the high lumber prices are due to Trump’s tariffs. To an extent, yes, but look at the following graph. Lumber prices did shoot up in 2021 after being fairly stable during the Trump Presidency. The modest run-up in early 2018 was followed by a rapid decline. The tariffs didn’t seem to work.

So what explains the increases in 2021 and 2022? The key driver has been Federal Reserve monetary policy of monetizing the Federal government’s debt. There have been two other forces that have contributed: the COVID-induced lockdowns caused many to go on a home improvement spree, increasing the demand for lumber; and very wet weather In British Columbia that precluded lumber being shipped to the mills. The tariff were bad, I was against them when they were proposed in 2016. However, President Biden announced that they are being rolled back. If they were the cause of the high prices then we would have seen a decline in prices. (The futures price of lumber shows the same basic shape, implying that the market doesn’t believe the removal will offset the inflationary pressures.

Tariff and embargos cause prices to be higher but not rising. There is a difference between a high price and a rising price. Again, inflation is price changes in the aggregate, not individual prices which change all of the time.

While the freighters off the coast of California make great copy for the nightly news, they don’t explain inflation. Prior to the focus on them, does anyone reading this know what the average length of time a freighter was idling or, more importantly, what this is doing to the prices of goods? People didn’t buy goods from Asia but bought them from Europe. There are substitutes for everything.

So, my friend’s case against Trump fall flat. What, then, does cause inflation. Let’s start with the Quantity Theory of Money. It is a tautology but can be made to give insight to the working of the economy. It is:

M * V = P * Y,

or the money supply, M, times the velocity of money, V, (how fast it turns over) = the price level, P, times real GDP, Y.

By doing some mathematical manipulations that you needn’t concern yourself with we get that the percentage change in M + the percentage change in V= the percentage change in P + the percentage change in Y., that is,

%change in M + %change in V = %change in P + %change in Y.

If we re-arrange this, like so:

%change in P = %change in M + %change in V - %change in Y

It is clear what the real drivers of inflation are. As Milton Friedman correctly told us back in 1963: “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.” Assume for a moment that V is constant (it isn’t, but it isn’t typically a real driver of inflation, except during hyperinflations). If M and Y grow at the same rate, inflation will be zero. If M grows faster than real output, inflation will be positive. A worse case is when M is increasing while Y is decreasing. Both are working to increase the inflation rate. (The worst case scenario is when V increasing along with increases in M and decreases in Y. This leads in the extreme to hyperinflation such as the Weimar Republic experienced in the early 1920s and Venezuela recently.)

Unfortunately, the worse case scenario is the situation today: we have arbitrarily reduced oil exploration and incentivized people not to work, both of which reduce Y. At the same time, the Federal Reserve is expanding the money supply by huge amounts. Even though the Fed says it intends to raise interest rates this year and it has belatedly recognized that this inflation isn’t transitory, it still continues expanding the money supply. Interest rates are going to go up this year regardless of what the Fed does due to inflation. We are going back to the late 1970s.

What can be done? First, the Fed has to stop buying securities which increases the money supply. It should start selling securities from its portfolio and shrink its balance sheet. Let interest rates be determined solely in the marketplace. The Federal government needs to reverse all of Biden’s anti-energy orders. Get rid of as many tariffs as possible. It needs to make the Trump tax rate cuts permanent. Continue the Trump policy of eliminating two regulations for every one added. I would go further and have every regulation subjected to review to see if they still make sense.

Unfortunately, once inflation gets rolling it isn’t easy, fast, or painless to stop it. The next eighteen to twenty-four months will be a struggle. If the changes suggested in the previous paragraph are not acted upon, inflation will remain with us, possibly getting worse and the economy will slow down. We will be reliving the 1970s stagflation again.

"Whither Oil Prices"

by Jim Mulcahy

November 15, 2011

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

Every time there is an oil price spike as there is today, two things happen. First, various government agencies launch investigations to see if there has been something nefarious going on. Second, despite the clamor for more drilling in the US, it is said that doing so won’t affect oil prices today. This is always used as the argument to allow the rabid environmentalists to continue to keep the most likely places to find oil off limits. The first is a silly waste of time. Not once has manipulation of the markets been discovered. The second deserves closer scrutiny, though.

Let’s say that is autumn and the wheat crop is in for the year. You have bought it all up with the intent of releasing it into the market in such a manner as to maximize your profits. With interest rates being positive the most will be released in the first month and the least in the final month before the next harvest. (I’m assuming that there isn’t any seasonal variation in the consumption of wheat. If there was the amounts would be adjusted accordingly. Ignoring it doesn’t change the qualitative results, though.) But now something terrible happens. The Argentine and Australian wheat harvests are expected to their best ever. They will have sufficient quantities to sell into the US market. This wheat will come onto the US market in six months.

Clearly, you won’t be able to sell the wheat you had planned to sell in months 7 – 12 for as much as you had planned. What to do? Being rational, you will want to increase the quantities you sell in the first six months, even though it will result in a lower price. You will do this because it will enable you to maximize your profits (which will now be lower than they had been expected to be before the bumper crops elsewhere) under the new price-quantity combinations that are expected to prevail. Note that while the Argentine and Australian crops haven’t arrived yet the implications of their impact on prices have been factored into the plans of the holder of the US wheat. The rational response is to recognize that the inventory is now less valuable and the needs to be sold sooner even though it means receiving a lower price.

Wherever you see (U)S wheat replace it with OPEC oil. Wherever you see Argentine and Australian wheat replace it with US oil. The analysis is exactly the same. If the government allowed our oil firms to explore in the currently off-limits areas where we know there is plenty of oil, the current price of oil would decrease. It would do so as OPEC realized that its inventories of oil are now less valuable than they were before. In order to maximize their profits they will supply more oil into the world markets today. This is a critical insight. The expectation of more oil (or wheat) will cause the current price to fall from what it would have been.

The lower price of oil will be an enormous increase in the discretionary incomes of Americans, far greater than any targeted tax reduction would be. It would reduce our Balance of Payments deficit. It would employ, at rather handsome wages, many people. It would reduce the incomes of some of the most unstable and mischievous regimes on the planet. It is difficult to see why our political leaders continue to allow a small but vocal minority negatively impact our lives.

"To Extend or Not to Extend"

by Jim Mulcahy

November 30, 2010

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

As I write (Nov. 30, 2010) the Congress is about to start debating whether or not to extend all of the Bush era tax cuts or just a subset of them in order to deal with the deficit. The Republicans want all of the current tax rates to be continued indefinitely, that is, until a real overhaul of the tax code could be tackled. They appear to be willing to settle for a minimum of a two year extension. The Democrats, led by President Obama, want the current rates continued except for those making over $250,000. Senator Chuck Schumer, of NY, put forth the option to extend the rates for everyone making under $1,000,000. The public, that is, us, prefer to extend them for everyone. The reasoning underlying the Democrats views’ is suspect at best. Obama says we can’t afford them, and it will only affect 2% of the taxpayers. These 2% pay about 45% of all income taxes; the bottom 50% pay 3.5%. Looked at another way the top 2% are paying 13 times as much as the bottom 50%. As it stands the top 2% are certainly contributing heroically to funding the government. Let’s look at the charge that we can’t afford not to raise the rates. As is usual in government, when one is trying to make a point the cost/savings for multiple years are given because it balloons the figure. We can’t “afford” maintaining the current rates for everyone else either, on their reasoning. One factor, and it is a big one, that the Dems have overlooked is that those in the top bracket aren’t going to sit there to be shorn. They will alter their behavior and reduce their taxable income. In effect, the increased tax revenue will be less than estimated, by a long shot. Further, in their efforts to reduce taxable income these individuals will spend resources to avoid taxes rather than devoting those resources to growing output.

We have the spectacle of columnist, Froma Harrop, shrilly saying that; “And what business is it of the chairmen — Erskine Bowles, a Democrat, and former Wyoming Sen. Alan Simpson, a Republican — to set an arbitrary (and low) maximum percentage on the tax revenue relative to gross domestic product that our society is allowed to collect? Their job is to find ways to bring down deficits. Period.”

She then goes on to say,

“For all the talk of the painful, painful(!) sacrifices needed to achieve the chairmen’s goal of reducing the federal deficit by $4 trillion through 2020, one thing should be kept in mind: Simply ending all the George W. Bush tax cuts would do the same thing. No one starved in the Clinton era. In fact, people did darn well then. That’s something for Democrats to think about now, before Republicans take over the House and start the fiscal voodoo dance all over again.” You can’t make this stuff up. I’m always amused by liberals/ progressives belief that 50.1% of us should be able to tell the other 49.9% what to do when it suits them. The Bill of Rights were enacted precisely because the Founders recognized that the likes of Ms. Harrop were lurking out there. Survey after survey shows that most Americans, 70% or more, believe that an individual’s total (State, Local, and Federal) tax burden shouldn’t exceed 25%. These results hold for every subgroup out there . Well, almost all. I’m sure that the polls don’t have subgroups for: clergy (of any denomination); college English professors; carping liberal columnists; or unionized government employees. These would demand expropriation of all income from those who made more than they did. This is typically their definition of “the rich”.

Turning to Ms. Harrop’s comparison with the 1990s. It is a totally inappropriate comparison. Ms. Harrop confuses correlation with causation. To start with, the economy was still in the glow of the Reagan years. The benefits of increased investment were still accruing. Lawrence Meyers, who Clinton appointed to the Federal Reserve Board, had an economic consulting firm that analyzed the Clinton tax increases. Their conclusion was that the economy grew slower and total taxes collected were lower than they otherwise would have been. So, in fact, the Clinton higher tax rates weren’t a boon to the economy. They didn’t appear to be a bad thing because of other decisions that were being made. The two most important were the election of the Republican majorities in 1994 that slowed the growth of government spending and the slashing of the capital gains tax rate, against Clinton’s wishes, by the way. These two events, against the backdrop of the Reagan growth agenda of the 1980s more than swamped the negative effects of the Clinton tax increases.

Sen. Schumer defends his proposal by falling back on the most naïve version of Keynesian economics. He still believes in the concept of the marginal propensity to consume out of current income, fifty some years after Milton Friedman showed that people consume out of permanent income. He seems to believe that if we just put more money into the pockets of people with high average propensities to consume the economy will grow. Two problems with that: first, most obviously, we have been doing that for two years and have nothing to show for it; and second, what is being discussed by the Congress is not a tax cut but the prevention of a tax increase, which even Schumer realizes would be a disaster.

The Republicans push for maintaining the current taxes for everyone reflects the understanding that investment and job creation come from those making more than $250,000. From a supply-side approach, the response to incentives is very disproportionately from the higher income small businessmen and other entrepreneurs. Lowering marginal tax rates typically doesn’t cause a bank clerk, say, to increase their level of economic activity while it will to a business owner, or potential business owner.

Obama’s attitude was put on display during the campaign when he responded to Joe the Plumber, saying that he was for redistribution. Raising rates for the so-called rich (m any two income families in NYC would fall into this definition of rich) appeals to his political orthodoxy which trumps his obligation create an environment in which the economy can grow.

When the dust settles where will we be? I expect that the tax rates for all will be extended for at least two years and as a quid pro quo, unemployment benefits will also be extended for another 26 weeks. It is important to keep in mind that this will only prevent things from getting worse than they are. In order for the economy to gain real traction, the plethora of mandates and regulations spewing out of the Executive branch must stop and many need to be repealed. Simply put, regulations have the same effect as taxes but don’t get run through the government income statement. The EPA, Health and Human Services, and the Dept. of the Interior are loose cannons that are circumscribing our daily lives to our detriment. The Health Care bill needs to be rescinded and begun anew. The financial reform legislation, another unread 2000+ page monstrosity, needs to be put in abeyance while cooler heads revisit every provision. The energy drilling moratoria across the country need to be reassessed.

The vote on the tax rates will give a clear picture if the Congress got the message that the “Tea Party” sent on November 2. If they didn’t the message , be prepared for another housecleaning in 2012.

"Stimulus II - Beyond Parody"

by Jim Mulcahy

9/9/2010

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

I have always found it odd that Democrats, in particular, push for fixing roads and bridges during a recession. They quote studies that say our infrastructure is crumbling which, I’ll agree, is probably correct. However, it was crumbling even faster before the recession when it had more vehicles plying their way across it. Where was the concern, then? If the recession hadn’t occurred they would be in even worse shape. Obama also mentioned redoing airport runways. Are we to understand that planes are landing on crumbling landing strips. Where are the FAA and the transportation safety boards? The railroads are also being included in this spending spree. I thought they were privately owned. .

Government bodies have done this for years: pushing off maintenance and repair because doing it would require either raising taxes or, shudders, restraining spending elsewhere. Runways, roads, and bridges are physical capital that need to be maintained and upgraded on a regular ongoing basis, not an episodic one whose primary goal is to obtain votes or campaign contributions. .

Attempting to use infrastructure projects to boost the economy is doomed to utter failure. A critical complaint about government spending to counteract recessions is the lag between the approval of spending funds and the actual spending. Infrastructures are at the extreme end of this spectrum. By their very nature they are long-lived with the funds entering the economy relatively slowly. This round of projects is to be a six-year endeavor. The unemployed won’t be with us if they have to wait that long for the economy to turn around. .

A second point is the question of whether or not we should put all of our stimulus funds into one sector: civil engineering projects. On the margin does the citizenry think this is the most critical area to devote resources to, today. I don’t know the answer, and it is doubtful we will ever find out. A third point is that these big infrastructure projects are not very good at getting people back to work. These projects tend to be very capital intensive so that for any given amount of stimulus dollars spent they increase employment less than many other activities would. .

The upshot is that the politicians are continuing to treat the populace with callous disregard by their dereliction of responsibility to keeping the roads, bridges, and runways at acceptable levels of repair. (Would a private insurance company be willing to underwrite coverage on some of these roads and bridges?) The spending of the $50 billion won’t impact employment or GDP now. It may add excess demand for resources in three years when the Fed is trying to slow the economy. The only things that it can be assured of doing are increasing the national debt and giving politicians talking points. It would be funny if it weren’t so sad. .

"Are All Deficits Created Equal?"

by Jim Mulcahy

9/1/2010

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

One of the ongoing debates in Washington and throughout the Land is whether we need a second dosage of stimulus. By all accounts the first one has been a colossal bust, Joe Biden and Robert Gibbs notwithstanding. Over $800 billion was budgeted: on top of the TARP, GM and Chrysler bailouts, and the never-ending Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac trips to the Treasury’s ATM to address the dramatic economic slowdown. This recession is the worst since the early 1980s. The responses to each are instructive.

In the 1981-82 recession, President Reagan made two critical choices. First, he supported Fed Chairman Paul Volker’s efforts to bring inflation down from its, by US standards, outrageous rate of 13%. This courageous act extended the recession but helped lay the groundwork for a quarter century of prosperity. Secondly, he cut tax rates. More precisely, he slashed the tax rates. Individuals and businesses now kept a larger share of what they produced. The tax rates didn’t kick in until 1983 so people deferred activity from 1982 until then, thus making 1982’s performance worse than it could have been. Tax revenues rebounded over time even though the deficit rose initially. (To be sure, Congress couldn’t restrain the impulse to spend the gusher of revenues.) Over the 1982-1988 period, the American economy grew by one-third(!) – the equivalent of annexing West Germany. The key was that the government didn’t suppose it knew best as to what activities and actions would be the most productive. It left those decisions to the individual firms and citizens. Clearly, it worked well.

Fast forward to today. The President and the Congress have earmarked most of the funds to prop up profligate state and local governments and school districts. These funds were used to prevent layoffs. There were going to be layoffs because the public sector unions REFUSED to forego pay increases, even while 55% of all Americans had either lost their jobs or had their pay reduced in the past two years. Anecdotes are rife about the callousness of the union leadership when it came to adapting to the new reality or throwing some members overboard. The real issue is whether these subsidies to other government units will result in the economy growing. To date, they haven’t. Joe Biden is reduced to touting the fact that two hundred thousand homes have been weatherized. Wow! There are over one hundred million homes in the US. You do the math on when this will be complete. I don’t need to remind you that these weatherizing programs have been notorious for their shoddy workmanship and flagrant theft over the years.

The premise underlying the Keynesian models that are being used by the administration and the pundits supporting them, personified by Paul Krugman, is that it doesn’t matter where one puts another dollar into the economy as long as another dollar is put in. I doubt if Keynes himself believed this. Resources need to be put to their highest valued uses if an economy is to prosper. The Harvard economist, Robert Barro, has shown that the government multiplier effect is, at best, about 1 and often below 1. For those who remember their introductory economics, a multiplier greater than one is the holy grail of government spending: take a dollar from individual A and give it to individual B and, voila, there is now more than a dollar of output. This is alchemy at its best.

Current macroeconomic research shows that the problem with most advanced economies such as ours is not the lack of sufficient demand but the relative dearth of investment, productive investment. Building more homes barely qualifies as productive investment, especially when at the margin those who were induced to buy one can’t afford them. This is the 21th century version of digging a hole and filling it back in. Government policies: the tax subsidy to home ownership; the community reinvestment act (CRA); HUD policies in the late 1990s; low interest rates from the Fed; and congressional meddling (read: Barney Frank); all contributed to the massive over-investment in housing. This mal-investment, if you will, now needs to be wrung out of the system. Since houses are long-lived assets this will take awhile.

Another key component of current macroeconomic thinking is that expectations of what the future will bring matter. Markets do not like uncertainty, either. The expected return of higher income tax rates in 2011 has influenced decisions. Projects that look marginally profitable today will be under water with the higher taxes, so these projects get shelved. The quagmire known as the health care reform act continues to causes firms to cringe as more of its details become known. While many of its mandates aren’t direct taxes; that is, they won’t show up in the government’s financials; they act like taxes, thereby reducing economic activity.

Recoveries tend to mirror the decline: if the latter was sharp, the former also tends to be since there is significant slack that can be easily absorbed without creating bottlenecks. That is another reason this recovery is so troublesome. The economy hasn’t bounced back and has slowed precipitously so far this year, in spite of the massive injections of money that have ballooned the deficit. Increasing the deficit with no prospect for growth to generate the revenue to pay for it is a recipe for disaster.

Germany took the tack opposite that of the US. It lowered tax rates and reduced regulations and it did not spend itself silly. Its recent growth, as that of many other European economies, has dwarfed that of the US. It is said that Albert Einstein defined insanity as doing the same repeatedly and expecting different results. The Administration has obstinately clung to its approach, despite its abject failure. The failure is clear from the current results. A comparison to the 1981-82 recession, and the results coming in from elsewhere around the world indicate that the approach the US has taken is seriously flawed. We can have deficits either with increased government spending on projects that pass the political test but not necessarily the economic test, or we can have deficits resulting from reduced tax revenues due to lower marginal tax rates. The latter is the preferred approach if the goal is to return the economy to its long-run growth path.

"It's the Yuan's Fault"

by Jim Mulcahy

May 27, 2010

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

The Chinese currency, the Yuan, is the current whipping boy for the fact that the US is running an enormous Balance of Payments deficit on its Goods and Services account. This is the sub-category that gets all of the attention since the unions and big businesses are most affected. It has become an article of faith, or urban legend, that the Yuan is undervalued by 40% due to currency manipulation by the Chinese government. The implicit assumption is that if the Yuan were just permitted to find its true equilibrium value, assumed to be 4.8771 Yuan/$ based on the May 26th closing price of 6.8293 Yuan/$, then all of the manufacturing jobs that have disappeared over the past decade or so would return to American shores.

Not so fast. A little history will show the tenuousness of this assumed sequence of events. In the 1980s, Japan was the whipping boy for the decline in manufacturing jobs in the US. It is important to note that the issue that most vexes people (read: unions, politicians, newspaper columnists) is the decline of union jobs. Manufacturing output has continued to rise over time, by the way, although one would never realize it from the press reports. Using the 2002 annual average as the base, that is, setting it equal to 100.00, Industrial Production in the US rose from 60.9454 in January, 1985 to 112.3962 in December, 2007. It currently is 102.2666. From January, 1985 to December, 2007, then, output increased by more than 84%. It is down 9% due to the recession.

In January, 1985, the US-Japan exchange rate was 254.1829 Yen/$, that is, the US had what was considered to be a very strong currency. Japanese products didn’t cost all that much, relatively speaking. The Balance of Payments that January was -$3.868 billion. In December, 2007, the exchange rate was 112.4490/$. This means that Japanese goods now cost 2.26 times as much in US dollars as they did in 1985. This nets out the effect of inflation in both countries. The Balance of Payments was -$6.578 billion. As of March, 2010, the exchange rate was 90.7161 Yen/$. The Balance of Payments was -$5.317 billion. Hmm? Japanese goods became more expensive and, yet, we ratcheted up our consumption of them. This wasn’t supposed to happen, was it? What went wrong?

The fundamental problem is that the prognosticators either didn’t read their Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, or have forgotten it. Implicit, also, in their assumptions is the belief that the Chinese, like the Japanese were supposed to, won’t adjust to the new prevailing set of prices. They will be happy to have reduced demand for their production, thus accepting a lower standard of living. As can be seen from the Japanese-US results, the Japanese became much more productive, aggressively so. It is entirely likely that this situation will be repeated in China. In fact, since China is starting from a much lower base of productivity, they have the ability to make even greater proportional improvements in a short period of time. The end result of our browbeating the Chinese to revalue their currency to a rate that we would prefer is that we will have caused them to become an even more formidable competitor, especially in markets besides ours and theirs.

The other aspect that the pundits forget is that the US is not the only trading partner China has. This is true for virtually every country. A country buy inputs from some countries and sell finished goods to others. Inputs and finished goods mean different things to different countries. Australia is a net exporter of raw materials. These are its finished goods. Their inputs are the heavy equipment they acquire to mine the ores. In China or Japan’s case, they acquire the ores and manufacture consumer products. China and Japan will run trade deficits with countries like Australia, while running export surpluses with countries like the US. The appreciation of the Yuan may reduce China’s overall balance of trade surplus but it doesn’t guarantee that the deficit with any specific country will be reduced. As we saw with Japan, the enormous appreciation of the Yen did not make a difference to its trade balance with the US.

Our pundits seem to believe that one can legislate prosperity and cause the return of manufacturing jobs to the US regardless of the efficiency with which that output is produced. It is stunning how little we have learned from our previous attempts to legislate an economic nirvana. Ohio and Michigan lost many manufacturing jobs in the early 2000s. No one seems to have connected the dots and observed the relation between our imposing steel quotas, designed to protect a small number of steelworker jobs, and the ensuing uncompetitiveness of our much more numerous steel using industries. Successful firms and industries are those that have recognized that increased productivity is the only way to prosper in a world where consumers want the best quality for a given price, or the lowest price for a given quality.

Bashing China and its exchange rate policy will not improve our manufacturing employment base. It may, however, cause it to dwindle further. Be careful of what you wish for.

"Here Comes the VAT"

by Jim Mulcahy

April 25, 2010, 2010

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

When I was a youngster, I went to see Cecil B. DeMille’ movie the Ten Commandments. I was capti vated by one character, in particular. This was the angel of death. For those unfamiliar with the story Moses is attempting to convince the Egyptian Pharaoh to free the Israelites from bondage. He brought down nine plagues upon the Egyptians due to the Pharaoh’s intransigence. Actually, God brought forth the plagues; Moses was just His mouthpiece. Finally, God gave the Biblical equivalent of the nuclear option: death to the first-born of the Egyptians. He instructed Moses to mark the doorways of the Israelites’ homes with lamb’s blood so the angel of death would pass by these dwellings. This is the origin of the important Jewish feast of Passover. In the movie the angel of death was portrayed by dry ice. It created a mist-like cloud that wound its way through the streets wreaking its vengeance on the Egyptians. It was a silent, insidious killer.

What does that have to do with the VAT, value-added tax, you may ask? In my mind, the VAT is a silent, insidious killer, too. While the angel of death was doing God’s work, though, the VAT is more akin to satan’s.

The incessant rumblings about considering the imposition of a vat in the US are due to the federal government’s need for staggering sums of tax revenue. I’m not engaging in hyperbole here. Even eighteen months ago the sums required would have been inconceivable; not so, today. Congress and the president have obligated the US taxpayer beyond what is collectible from the income tax code. The irony here is delicious: the pock-marked (read: loophole or exemption ridden) code will now prevent the government from generating sufficient revenues. A simpler tax code, a flat tax would be best, would generate the most revenue and allow the economy to produce at its maximum capacity. Unfortunately, a flat tax eliminates the ability of politicians to buy votes by granting exemptions for whatever “worthy cause” is groveling for favors.

A good tax needs to have three characteristics: 1) it needs to be transparent; that is, one should be able see the amount of the taxes collected. The income tax code is the exemplar. Nothing is hidden; the code may not make any sense but one can easily see what he is paying; 2) it should be broad-based so that arbitrary exemptions are eliminated; and 3) it’s rates should be low so as to minimize the distortions that any tax will cause. The VAT fails completely on the first characteristic. It is the angel of death: a silent, insidious tax. It is nigh onto impossible for a consumer to determine how much of the price of a good he is buying represents taxes. This is one reason politicians like it; it is hard to trace it back to them. It is broad-based but for the wrong reason; it is such so as to collect as much revenue as possible. Given our political will it will become pock-marked, too. Finally, it won’t be low. It will generate scads of money and this will enable politicians to engage in their favorite pastime: buying votes. The politicians won’t be satisfied with funding the current panoply of programs that are bankrupting us, they will conjure up new ones.

It is important to realize that it will NOT replace the income tax, especially considering that 50% of Americans pay zero, or less, in federal income taxes. As such, it will be a close to a 20% decrease in the standard of living, if we use the average European rate. I say close to because it will fund the many goodies that emanate from D.C. If Americans were given the opportunity to buy these goodies from govt., Inc. they would, in many (most) instances opt not to buy them or buy them in vastly reduced quantities, but they would buy some of them.

Let’s look at the comparative economic performance of the European community, specifically: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovak Republic, and Spain; with that of the US over the 18980-2008 period. In 1980 the European community, vat taxers par excellence, had 118 million people employed. Twenty-eight years later employment was 143.2 million, an increase of 25.2 million. Germany and Spain accounted for 11.8 million of this increase. The percentage increase was 21.4%. Turning to the US, its employment was 90.5 million in 1980 and 136.8 million in 2008, an increase of 46.3 million, or a 51.1%. In the US tax rates were cut over most of this period, while the Europeans continued to levy the insidious vat. It doesn’t take a social scientist to be able to discern which one did better. Spectacularly better, I might add. Raising tax rates has never reduced the deficit. The budget surplus in the Clinton years was due to the decrease in the capital gains tax rate, which Clinton opposed by the way, that generated a veritable gusher of revenues. In the Reagan years the tax rate cuts increased the tax revenue substantially, even though Congress couldn’t resist spending even more. Similarly, Margaret Thatcher’s tax rate cuts in the UK brought prosperity. Politicians don’t like self-generated prosperity since no one will turn to them for help. They will have become redundant at best.

An unintended consequence of imposing a vat in the US is that it will make foreign goods cheaper. You may counter,”no, they will be taxed at the checkout point, too.” Ah, yes, those goods that are imported to the US will be but not those consumed outside the US. We can expect to see fewer vacations to Florida or other US destinations and an increase in trips abroad, since the latter will now be relatively cheaper. Never underestimate a politician’s ability to not think ahead and examine the secondary impacts of decisions.

I think it goes without saying that I’m not a fan of a vat. In order for the US to continue to prosper and grow, it needs to reduce tax rates and cut spending across the board.

"Has the Property Tax Outlived its Usefulness?"

by Jim Mulcahy

March 7, 2010

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

In the March 6, 2010 the Weekend edition of the Wall Street Journal had an article with the headline: “Homeowners Hold Ground Against Rising Property Taxes.” California’s Proposition 13 from the late 1970s is now working its way across the US. People are beginning to vote with their feet to escape the impact of high and rising property taxes. The property tax has evolved from an efficient means of generating the required revenues to provide necessary community services to a means of generating enormous sums of revenue to spend with little thoughtfulness and care, compared to how the taxpayer would spend the monies, on an ever expanding and well-heeled bureaucracy.

Approaches to taxation over the centuries developed based on the ease of collection and the broadness of the base. For instance, at the founding of the U.S. most taxation was on imports or exports. This was due to a number of reasons. It was easy to determine the value at the point of embarkation. Most people, if they were paid at all and didn’t engage in some form of barter, were paid in cash for goods or services rendered. This made it difficult to track incomes. It wasn’t until the twentieth century when the Progressives (Socialists, by another name) convinced enough people that it was somehow inherently unfair that a subset of Americans were rather well-to-do and should be made to pay “their fair share.” At its inception the income tax was applied to less than 1% of the population and wasn’t used to fund utopian schemes. How times have changed.

The property tax had much the same evolution. When governments were small, people fended for themselves, and the tax rates were low and reflected, however imperfectly, the services rendered to the homeowner or business. That has all changed. Property taxes and their abatements are used shamelessly by local governments to hand out largess, in one form or another, to favored constituencies. Typically, the largess has gone to commercial and industrial firms that threaten to leave town. The politicians are to blame for causing this state of affairs because of the discriminatory rate of taxation they impose on businesses.

In my home town the busybodies at the economic development board want to encourage more commercial enterprises to locate here. Why, you ask? This is their stated reason, I couldn’t make this up if I tried: commercial enterprises receive $.52 in services for every $1.oo in property taxes they pay. Homeowners get $1.07 for every $1.00. Therefore, if we get more commercial businesses here we can subsidize the homeowners even more. Would anyone pay $50K for a Toyota Camry that could be purchased in another town for $26K? Of course not, but this is the type of behavior that this board thinks exists. And they wonder why it is difficult to get firms to locate here unless they are given tax abatements galore.

The important point, though, is that property taxes no longer bear any relation to the services rendered to a piece of property. As a simple example, take two homes that are being built on adjacent lots. Both homes are of the exact same size and layout. The first owner decides that he wants to put in the best appliances, heating system and water heating system possible. He still has one kitchen, one furnace, and one water heater just like the guy next door. To make the differences in value even sharper, the first owner has gold faucets placed in the master bathroom. Clearly, the cost of this house will be greater than the second one. Its property taxes will be higher, possibly much higher. Just as clearly, the first house receives no greater or better services for this increased taxation.

The property tax is a fixed cost to the property owner. It must be paid regardless of the owner’s fiscal situation. Because of this municipal employees have no reason to moderate any wage or benefit demands. Only in those locales where one very large industrial plant, although these are becoming few and far between since the golden goose of steel mills and auto plants has been killed, pays a preponderance of the property taxes and can move operations elsewhere, is there any moderation in demands by the municipality.

In economics, a decrease in income would cause an individual to reduce consumption of every good, some more, some less severely. However, the property tax compels one to consume the same amount of government provided services, making all of the reductions in privately provided ones. This sends distorted signals to the marketplace, and in particular, to the politicians. In the short-term this game is assumed to be played successfully by municipalities but over time as fewer firms set up shop in the area, the more talented young people leave before they become too committed to the locale, it is clear that the politicians won the battle but lost the war. Over time, then, the community slowly deteriorates. Once this starts it takes a very long time to reverse the cycle.

It is high time that the property tax be completely rethought and reduced in significance as a source of tax revenue.

"Are Tighter Reserve Requirements the Answer to Mr. Bernanke’s Dilemma?"

by Jim Mulcahy

February 6, 2010

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

In the February 3rd edition of the Wall Street Journal, Andy Kessler lays out his preferred approach for Ben Bernanke and the Fed to unwind the monetary stimulus they have injected into the banking system in the past two years. This stimulus has been staggering. The monetary base, the part of the money supply the Fed actually controls, has ballooned from $850 billion to $2 trillion. Not exactly chump change. Mr. Kessler believes that the Fed should increase the required reserve ratio, the percentage of deposits that a bank must keep on hand: that is, the percent they can’t lend out; by 1% per year until it hits 20%. This would dampen the effect of the fractional reserve system we have. Since the ratio is about 3% now, this will take 17 years or two business cycles to complete.

This isn't a new idea. Usually, though, people follow it to its logical conclusion: 100% reserve money, or something akin to a gold standard. With 100% reserves, a bank could only lend out their own funds, debt or the deposits, but not a multiple of the deposits. Without going through the math, a fractional reserve regime allows the banking system to lend out 1/reserve ratio it has as initial deposits. If the reserve ratio is 8% then $1 of deposits could support a total of $12.50 in loans, $1/.08. This is, in effect, increasing the money supply by $11.50.

A one hundred percent reserve policy would eliminate the fractional reserve banking system. It would cause an increase in the velocity of money and/or cause prices to decline (including wages) and cause trade credit to expand, as would any decrease in the money supply. Now, if there would be a jolt to the system (not all jolts are monetary) trade creditors would bear the brunt. Since they tend to have narrow focus's - lack of diversity in assets - they could be clobbered. Banks tend to diversify their assets because their expertise is in risk evaluation. Trade creditors are just trying to move product out of the factories.

The author understands how fractional reserve banking got started but doesn't seem to understand that Goldman Sachs, Lehmann Bros., etc. couldn't engage in it because they don't have demand deposits, only commercial banks do. Investment banks can’t create money! While people may grouse about Goldman’s knack for “printing” money, that isn’t the same thing. The fact that investment banks were very highly leveraged doesn’t derive from any reliance on fractional reserve banking.

Mr. Kessler’s approach is completely wrong to implementing a higher reserve ratio. It is a classic case of the law of unintended consequences. If banks knew that the reserve ratio was going to climb in the future they would lend like mad today, allowing the natural runoff of the loans to bring them into compliance with the higher ratios in the future. This would balloon the money supply causing prices to rise rather substantially, igniting the inflation that he wants to avoid. It would be followed by a recession as the money supply decreased but individuals didn't believe that the cycle wasn't going to repeat itself. For those of us old enough to remember, this is just the Carter years revisited.

It would make more sense (but see below) to immediately raise the ratios to effectively sop up a portion of those excess reserves sitting on banks' balance sheets. However, this doesn’t address the real problem: the creation of the excess reserves. As long as the Fed pumps reserves into the banking system the multiplier effect exists with any fractional reserve system. It may be lower with a 20% reserve ratio than with a 10% reserve ratio (and, of course, it is higher than larger one) but it is still there.

Since it would be unfair to jump to a 20% reserve ratio immediately because most of the banks in the US weren’t part of the debacle and adjusting that quickly would wreak havoc on them and their customers. The easiest way would be for the Fed to start selling those securities they purchased back into the banking system. This would be reversing the expansion process. Those banks with the excess reserves would see them decline. Other banks that do not have excess reserves wouldn’t be impacted.

Once the excess liquidity is sopped up then it would be time to seriously consider an 100% reserve requirement. Also, and probably more importantly, at that point the Fed should cease and desist discretionary open-market operations. Real per capita GDP growth in the US is about 2.25%. The Fed should add reserves to the system at an annualized rate of 2.0% each week. This wouldn’t be perfect but it would reduce the volatility in the economy emanating from the monetary sector to white noise. The Fed’s intervention would be limited to providing liquidity to sound banks that experienced a run. Any serious volatility would then be attributable to events in the real sector of the economy.

There is one final aspect which isn’t the Fed’s concern, directly, since their mandate is to maintain price stability, along with full employment. Banks are not eleemosynary institutions. They are there to make money. Reducing the extent to which they can expand the money supply will make them less profitable. As such, they will raise fees and interest rates and lower deposit rates. The marginal banks will fail. Thus, the banking industry will undergo accelerated consolidation. This may or may not be a good thing. However, those who are impacted will cry to their elected officials to “do something.” This will, without a doubt, be a bad thing. Politicians who by their nature do not understand economics or finance will concoct a solution that makes things worse.

Therefore, be careful of what you wish for. As Thomas Sowell has pointed out we need to think past stage one.

"It Must Be the Drinking Water"

by Jim Mulcahy

December 17, 2009

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

I am referring to the behavior of the folks in Washington, D.C. They are clearly bipolar. They profess to want to achieve a specific goal but every action they take is designed to thwart it. Specifically, I’m talking about the avowed goal of creating jobs that this administration has bleated on about incessantly. It says it wants to increase private sector jobs, especially in small businesses. It and the Congress’ actions, however, will do exactly the opposite.

We had the spectacle on the Sunday morning talk shows of Larry Summers saying on ABC that the recession is over, while on NBC, Christina Romer said that it wasn’t . Where is Harry Truman’s onehanded economist when you need him? At least, they weren’t proposing policies that were in direct conflict with each other, although if each believes their position to be correct they will ultimately have to.

As an aside, in the late 1970s, inflation was driving up interest rates and devastating the housing market (something is always screwing up the housing market, it seems) because of the restrictions on the maximum rate that could be charged for mortgages. At the time, six-month CDs paid more than a bank could lend the funds at. You can’t make this up on volume. The Carter administration, in particular the Secretary of HUD, Patricia Harris, was going to present to Congress their plan for getting mortgages flowing again. The economists at HUD proceeded to draft a position paper that said, in essence, that what was needed to get long-term interest rates down was for inflation to be brought under control. The way to do this was to slow the growth of the money supply which would reduce both inflation and expectations of future inflation. Unfortunately, Mrs. Harris had taken a fancy to the views of Leon Keyserling, one of the first members of the Council of Economic Advisors back in the late 1940s. Being an unrepentant Keynesian, his advice was to increase the rate of growth of the money supply thereby driving interest rates down, which would make mortgages affordable and available again. The lawyers at HUD who assembled her testimony strung these two totally incompatible views into one document.

You get the picture: one paragraph would say that the growth of the money supply should be slowed, while the next countermanded that advice. It went on like this through the whole document. Fortunately for the Carter Administration, Stuart Eizenstat read the testimony late on a Friday afternoon, it was to be given the following Monday morning, blew a gasket and had her appearance cancelled. This type of nonsense unfortunately occurs all the time down there.

But getting back to today. Open any graduate macroeconomics textbook and it is clear that in order to increase per capita consumption we need to increase per capita levels of capital, that is, we need to expand investment. Can anybody name any actions taken by this Administration or Congress that would encourage firms to invest? I say encourage because it needs to be made clear that the government cannot create jobs, it can only create an environment in which entrepreneurs will be willing to undertake risks. The government can, and usually does, take actions that severely reduce the incentives to undertake risks and create jobs.

The most obvious current deterrents to job creation are the health care bill and the cap and trade legislation. Both will have the effect of causing jobs to be located overseas, whether by American firms or foreign domiciled ones. The U.S. will be viewed as offering firms fewer opportunities to earn their cost of capital while at the same time imposing severe financial burdens that will have to be met irrespective of the levels of output. Both the costs for health care, and they are going to be much higher, and for cap and trade can be viewed as quasi-fixed costs. These are costs that must be paid if a firm wants to open its doors. By raising the hurdle, on the margin, firms will opt not to expand in the U.S. or opt not to locate here to start with. Clearly, both will be job killers, especially for small businesses who don’t have the ability to absorb upfront costs such as these.

There is another job killer stalking the land, I’m afraid to report. In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan reduced the capital gains tax from 70% to 28%. The U.S. economy surged in that time period, growing by a third. In the 1990s, Bill Clinton, against his wishes, signed legislation reducing it further to its current 15%. Tax revenue poured into Washington’s coffers to such an extent that we actually had a budget surplus for a fleeting moment. The clear evidence is that a low capital gains tax rate is good for capital formation. The President wants to increase the rate which is clearly counterproductive if he wants to increase jobs. And by jobs, I mean well-paying ones. If our sole goal is to drive the reported unemployment rate to zero, including discouraged workers, a two sentence law could accomplish that. To wit:

All foodstuffs sold in the U.S. shall be produced here. No mechanized equipment can be used in the production of foodstuffs.

While this will guarantee full-employment, it probably won’t guarantee full bellies. Our standard of living would revert to that of the early 1800s.

Congress recently voted to extend the inheritance tax at its current rate through 2010 after which it is to return to its pre-2001 level of 55%. Say what you will about the inheritance tax, it acts like a capital gains tax. If it is increased, capital formation is reduced. In this case it is a bit more insidious because it takes the form of allowing the existing capital stock to disappear via lack of reinvestment. Further, small businesses, those that are impacted by this legislation, will divert resources to tax and estate attorneys to devise ways to protect at least a portion of their life’s work.

I recognize that there are some very vocal opponents of eliminating this tax, Warren Buffet and Bill Gates, Sr. being quite prominent. I don’t understand Mr. Gates problems with it. Nothing by the way prevents anyone from writing the U.S. Treasury a check for more than legally obligated amount of taxes if they feel that they under-taxed. I do understand Buffet’s. His companies sell life insurance which is one of the preferred means of dealing with the tax bill. If the tax bite is reduced, so is the demand for life insurance. He also has another incentive for keeping it high. His firm acquires many privately-held firms. He offers shares in his firm in payment and is able to split, if you will, the tax saving from postponing its due date (the 3 Ls of taxes: least, latest, and legal.) The higher the tax rate, the more there is to split. If the tax rate was zero, these firms would opt for the highest cash offer which would mean Buffet might have to compete harder for these acquisitions. Unfortunately (for me), the inheritance tax is pretty much of a non-issue. As a matter of public policy, though, it is of great importance. The firms most affected by the tax are those that are most likely to invest in the U.S. They are the largest job creators, by a long shot, in our economy. I find it sad that our politicians will opt for a tax that really doesn’t generate that much revenue, while its impact is concentrated on some of the most productive people in our society. It garners headlines; it is making those “fat cats” pay their fair share, whatever that means (other than shilling for votes.)

As the economy slowly grinds forward in the coming year or so and one asks why aren’t things improving faster, one need look no further than the impact of health care legislation, cap and trade, and the increases in the capital gains tax, including the inheritance tax.

"Who Creates Jobs?"

by Jim Mulcahy

November 19, 2009

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

Who Creates Jobs?

The right answer isn’t the government. The government only can redistribute jobs from one sector or firm to another. They do this via taxation, making the taxed less profitable and subsidizing someone who is less efficient than the taxed. Nice, huh?

The government, though, through its tax and regulatory policies can either create an environment that encourages entrepreneurial activity or it can stifle it. Typically, it opts for the latter. It is easier to deal with (read: control) a handful of big entities: big business, large labor unions, etc.; that are beholden to the government than it is with an enormous group of smaller firms that don’t like to schmooze or be schmoozed by them. As such, most of the US’s economic policy is directed towards making life easy for large firms and, consequently, more difficult for small firms.

Regulation can be thought of as equivalent to a property tax; you pay it regardless of the income generated. Large firms can spread the costs of regulation over many more units than a small firm can. In fact, big firms like regulation because it allows them to compete with the more nimble small firms. Okay, then, who does create most of the new employment? Big firms employ a lot of people but that isn’t the same as expanding employment. It is small firms who tend to be in the growth stage of their life cycle and add employees as they grow.

A simple example will explain why big firms, on balance, won’t add employees. Think of the auto industry. I use this because most are familiar with it. Assume that all of the autos purchased are made in the US. Prior to the recession that was about 18MM vehicles. That is close to maximum that will be purchased every year. Most vehicles purchased now are replacements for ones that are scrapped. There is no need to increase employment in this industry if the total volume of output is constant (maxed). However, if the manufacturers want to give raises to their employees without having to raise prices, which they couldn’t do very well in a non-inflationary environment, they will have to increase productivity. With higher productivity, it will require fewer workers to produce the 18MM vehicles. Therefore, it is easy to see that with increasing productivity the workforce at the auto plants will decrease. They will be well paid but there will be fewer of them.

On the other hand, small businesses will be expanding output and have a need for more inputs, especially workers. There are many more small businesses than there are big businesses, so if every small business hired even one additional employee the overall employment in the US would increase. It is also important to note that large businesses tend to be capital intensive, while smaller firms tend to be labor intensive.

Unfortunately, the government: federal, state, and local; inflicts policies that strangle initiative in the small business sector. They do this through a variety of mandates: health care, OSHA, workmen’s comp., building codes, etc. One can say that the workingman /woman needs protection from big bad businesses. I would submit that small businesses need protection from big bad mandates. The elected officials who pass these bills don’t bear the consequences of the damage they wrought. In fact, it allows them to come up with some additional legislation to address the damage. The option of repealing the underlying culprit would never occur to them.

If the US expects to recover from the current recession and expand employment opportunities on a more consistent basis, it needs to radically revise the way it addresses economic issues. It should do less, much less. I know that the knee-jerk reaction is for the government “to do something”, every time there is a hiccup in the economy. It needs to resist that impulse. The fix stays forever, even though the “crisis” has passed. The legislation should be designed to create a framework within which firms can compete on as level a playing field as possible. Most legislation is crafted for favored groups, regardless of the impact on the economy as a whole.

Doing less can result in much more being achieved.

"Jobs Saved"

by Jim Mulcahy

November 14, 2009

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

Jobs “Saved” When I use a word [number],’ Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, `it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.’ From ‘Through a Looking Glass’ by Lewis Carroll.

The endless repetition by the Obama administration about the near magical effects of the stimulus package brings to mind this passage from Lewis Carroll. Clearly, nonsensical jibberish has a long pedigree. The administration has gone to extreme lengths to justify/rationalize the stimulus package. For some inexplicable (to me, anyway) reason they have latched onto a concept they call jobs saved. Latched may be understating their devotion to it. There are two objections that come immediately to mind about it. The first is well stated by Professor Allan Meltzer of Carnegie Mellon University : ”One can search economic textbooks forever without finding a concept called ‘jobs saved.’ It doesn’t exist for good reason: how can anyone know that his or her job has been saved?” Simply put, this is something the administration has created on the spot. The second objection is empirical, which is to say the evidence that has been used to support the 650,000 jobs saved figure is laughable in the extreme.

It is disgraceful that a) the administration should expect their economic advisors: Larry Summers, Christina Romer, et al. who are very good economists; to go along with this nonsense and b) that they do. One can forgive Joe Biden for mouthing it, since he has a knack for getting things wrong and being arrogant about it. (One can stomach someone who is competent for being arrogant, but incompetent and arrogant is unforgivable.)

The growth or non-loss of jobs since February has been all in the government sector. Private sector jobs have shrunk every month. The only positive thing that has been said is that the rate of loss has slowed down. Whoopee, let’s hear it for that second derivative turning in our favor!

Now the Wall Street meltdown could, in my opinion, have been mitigated with much less pain if the Geithners’ of this world would having been willing to have a big bank or other financial institution go bust on their watch. Let them go bust on Friday and on Monday they’ll open for business under a new name. Life would go on. The keys in all of this are that in the private sector there are substitutes for everything, competition would force corrective actions to take place, and this episode was of a cyclical not secular nature.

The situation is diametrically the opposite in the public sector where the bulk of the stimulus money has actually gone. In this arena the problems are of a secular nature. Time isn’t going to cure them. Four or five years ago Business Week had an article about the coming public sector pension disaster. Politicians granted pensions and other retirement benefits that far outstripped their ability to deliver. These mistakes and the bloated labor forces have become albatrosses in more than a handful of states.

This current crisis would have been the perfect time to address these problems. Instead, the Feds slipped a two-year supply of methadone to these junkies so that they could avoid making the hard decisions that need to be made. A year and a half from now the problems will be that much worse and the adjustment that much more painful. Adjustments don’t have to mean people being laid off. They do mean that when a person resigns or retires the slot is eliminated and productivity increases. It means that raises are eliminated or reduced just like in the private sector for those who are still employed. It means that defined benefit pensions are frozen as of now and all future pension accruals are in the form of defined contribution plans, just like the private sector that has to keep topping off the public sector defined benefit plans even as their own 401Ks are tanking. This all could have and should have been done if the goal is to make our economy productive and competitive again.

In New York State where I live, the governor has sounded the alarm over and over again about the catastrophe otherwise known as the state budget. The legislature, led by Sheldon Silver, act as if nothing is wrong. They are out there re-arranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. Wall Street provided something like 40% of the State’s income tax revenue. That’s history. Goldman Sachs notwithstanding Wall Street won’t be as profitable as it was for many years to come if ever. Rich people have fled the state. Only someone seriously deranged or subsidized beyond recognition would open a business or expand one in NY. Most prosperous locales are living examples of Schumpeter’s creative destruction: some businesses, the less efficient ones, close, while new ones continually open. In NY businesses close but they aren’t being replaced by new ones.

This is the cost of “saving” jobs in the public sector. It prevents new ones from be created in the private sector and, ultimately, it won’t save the public sector ones either. The politicians in the states need to be held responsible for the terrible choices they have made in the past. Letting them off the hook will only serve to make the day of reckoning more severe. How will the administration explain those losses: jobs that didn’t disappear two years earlier because we increased the Federal deficit one more time?

Have We Finally Boiled the Frog?

by Jim Mulcahy

October 30, 2009

(note: This can also be seen on http://deepflies.wordpress.com/)

In a previous life I was a credit officer at a bank. When loan officers wanted to justify making loan by saying that “it is almost as good as one that was recently approved” I would tell them they are boiling the frog. The idea is this: a frog is a cold-blooded creature, so as the temperature changes so does its body temperature, as opposed to warm-blooded creatures that sweat or otherwise attempt to maintain a pre-determined body temperature. Placing a frog, then, in a pot of water of water and turning up the heat would cause the frog to adapt to the higher temperature: it would feel good. Turn the temperature up a bit more and the cycle repeats: the frog adjusts and still feels good. Eventually, though, the temperature gets to the level that the frog’s blood boils and it dies. The frog felt great until the end.

Hence my headline. I live in (the Peoples Republic of) New York state. Our budget crisis is staggering on any dimension one wants to contemplate. Tax revenues are down on cyclical basis, of course, but are also down on a secular basis, too. Despite the profits at Goldman Sachs, there are fewer Wall Streeters today than a year ago and they make less. Wall Street supported the spending urges of NY state politicians to the tune of about 40% of the state’s budget. The numbers are similar for New York City. Governor Patterson has sounded the alarm about the deficit that is approaching $10 billion over the two year budget period, even though (because?) the legislature taxed anything that moved or even threatened to move. He wants the legislature to impose spending cuts since the increased income rates have caused a number of rich New Yorkers to flee the state, notably Tom Galisano. Mr. Galisano co-founded Paychex in Rochester, ran for governor three times, and owns the Buffalo Sabres, a hockey team. He changed his legal residence to Florida saving (please be seated and have smelling salts handy) over $13,000 per day in NY State income taxes! This is income that is now taxed at 0% by the State of New York. Even the most mathematically challenged amongst us knows that zero times anything is still zero.

The legislature has avoided cutting spending, instead it increased taxes on a laundry list of items, many of which the citizenry could avoid by either not buying altogether or reducing the rate of consumption. These they did with a vengeance. As such, tax collections after the imposition of the new fees have lagged even further behind than the projections. The legislature won’t move.

Watching this train wreck unfold in slow motion over the past year I finally was struck by the realization that the legislators don’t seriously believe that anything they do in the form of raising tax rates, adding regulations ( hidden tax), or not addressing structural issues in the state’s budget will boil the frog. If they are stupid enough to believe that what they are doing will improve the lives of New Yorkers, they need to be institutionalized. However, I believe that they know that what they are doing isn’t helpful for the greater good but it does help get them re-elected and favorable coverage in the NY Times. They don’t conceive that their actions will be the one that get the temperature to the boiling point. A little more taxation won’t hurt; after all, this is America and New York, the Empire State, nothing can prevent us from achieving our destiny, whatever that is.

The legislators and their minions: state employee unions and do-gooders of all stripes; truly believe that even though this tax rate increase has detrimental effects, the economic prowess of New Yorkers will overcome it and grow the economy to new heights. Any discussion to the contrary is dismissed as the talk of greedy capitalists, people who don’t want to share the burden in the downturn.

The sad fact is that new business ventures don’t set up shop in NY unless the taxpayers lavish untold million in benefits on them. Our universities educate people that work in Texas, Illinois, Utah, and elsewhere, anywhere but NY. Well-to-do seniors flee to Florida to escape NY’s confiscatory income and property taxes. Many return to Canada for the summer but not to NY.

This problem has been the province of a handful of profligate state governments: NY, NJ, CA, and IL, to mention some of the worst; until recently. It has now come home to roost in DC. The US House and Senate and Administration seem to believe that no matter what program they inflict on the US economy, it will be able to shrug it off and keep increasing living standards for hundreds of millions of people here, as well as untold millions more elsewhere. How else can one rationalize deficit spending that is adding a trillion dollars per year to the national debt; or a cap and trade energy bill to correct a non-existent problem; or a health care plan that is so flawed and expensive that the house has to count part of the expenses in another part of the overall budget to make the arithmetic work?

These are not cruel people that wake up plotting the destruction of American civilization each day. Many may prefer that we were more like the Western European countries with a much larger presence of government in every decision. None, I don’t believe, want to destroy the wealth producing miracle that is the US economy. However, their actions are doing just that. They are boiling the frog, all the while thinking that “just a little bit more” won’t hurt.

My guess is that if these legislators and executive branch officials were confronted with the costs they impose on society and told if their actions worsened our lives, then it would come out of their pockets that they would be much more circumspect in their advocacy of higher taxes , more regulations, or more mandates. Both NY state and America are rich places with many people with incredible ingenuity but even here eventually the frog will boil.

Bank Efficiency Ratios

by Jim Mulcahy

January 27, 2009

This is a paper I wrote of which a slightly altered version appeared in the Friday, January 23, 2009 issue of The American Banker.

Efficiency Ratios: An Answer in Search of a Question?

A commonly calculated measure of bank productivity is the Efficiency Ratio:

Efficiency Ratio = Non-interest Expense/(Net Interest Income + Non-Interest Income)

Banks routinely include the results in their quarterly and annual reports. The real question is, “why?” My belief is that it is done because it is an easy-to-calculate number; anybody can do it. Nobody, though, seems to have asked, “What does it tell us?” Or more accurately, “Does it tell anything important?”

I submit that it doesn’t tell us very much. A simple example will illustrate my point. Take a bank that has three major departments: Retail Banking, Commercial Banking, and a Trust Department. The Retail Bank accounts for 45% of the bank with an efficiency ratio of 58%; the Commercial Bank, 35% and 43%, respectively; while the Trust Department represents 20% of activity with a 70% efficiency ratio. The Bank’s overall ratio is, therefore, 55.15%. Now, let Trust Department double in size while improving its efficiency ratio to 65%. The Bank’s overall efficiency ratio has deteriorated to 55.96%. Huh? According to the efficiency ratio measure that is reported this bank is developing a midriff bulge when, in fact, it is becoming leaner and more efficient.

The ratio is an aggregate that is a reflection of the current relative weightings of the individual departments. The operations of each department should be evaluated on their own, not blended into a puree that harms good performers and protects laggards. Further, a bank that gets out of the Trust business will see a marked improvement in its ratio, while a bank that adds a Trust department will experience the opposite. The ratio, though, is incapable of shedding any light onto the issue of whether or not the addition/deletion improved the bank; that is, benefitted the shareholders.

The emphasis on the efficiency ratio, clearly, is misplaced. It is part of a trend to become pre-occupied with FTE numbers1. As I said above, I believe that the ratio is calculated because it can be calculated. The example shows that the conclusion obtained, less efficiency, is completely opposite to that which is actually occurring. The situations when this measure provides accurate information are so remote that it should be eliminated from any analysis of a bank’s operations. In fact, the only situation where it is accurate is for an institution that hasn’t opened any new branches or added new products or services in years. Further, the growth rates must be the same across each and every existing product, service, and delivery point. Does this describe any bank in existence? In the branches, savings accounts require less non-interest expense than checking accounts. They look more attractive, then, than checking accounts. However, they require higher interest costs. Shareholders, ultimately, are only interested about net income. So which is the more attractive type of funding? It depends, of course. Economics tells us that as long as marginal revenue, MR, exceeds marginal cost, MC, the activity is worth expanding. If the MR

New branches or, for that matter, any new product or service are going to have initial phases where expenses are going to be high relative to income. This will negatively impact the efficiency ratio. A well-run bank should say, “damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead,” if these expansions are expected to result in Economic Value Added (EVAtm). Further, some products by their very nature, even at maturity, have a high proportion of non-interest expense to net income; think of the Trust Department or insurance operations. By the efficiency ratio criterion banks should avoid offering these products and services. Again, economics, to say nothing of common sense, tells us otherwise.

Obsessing over the efficiency ratio can cause a bank to take actions that are detrimental to its long-run profitability (the only kind that matters). Referring to the example above where the efficiency ratio worsened from 55.15% to 55.96%, a bank may believe that it needs to trim expenses. Assuming that the bank was being efficiently operated for its mix of business initially, then any cost-cutting will impair its ability to deliver quality service. Cost-cutting usually takes the form of letting staff go because it is the quickest way to jettison costs. There is that FTE mindset, again. This is a penny-wise, pound-foolish approach. Very little of the labor in banks can be considered a pure commodity. Most of the personnel have been trained in one fashion or other, most substantially: it may be external: a MBA or other academic accomplishments; or it may be bank-specific training that has helped create a culture and quality of delivery that sets the bank apart from its competitors. This human capital is the most valuable capital the bank possesses. None of these quality aspects appear in the non-interest expense amount in the efficiency calculation.

Again, what, exactly, is this efficiency ratio telling us? Is there any meaningful question; that is, one that would cause management to alter the way in which the bank is run; the answer to which would be the efficiency ratio? I didn’t think so.

It is time to stop calculating and reporting a number that is useless at best, and malignant at worst.

1Outsourcing is being done willy-nilly because it reduces head count. While certain activities clearly make more sense to be purchased on the open market, others are more appropriately done internally. In many cases working with suppliers can add value to the bank in excess of what could be achieved independently. See “The Supplier Equity Concept: Managing Supplier Relationships as Assets,” one of a series of executive development materials dealing with intangible asset management. By Robert E. Wayland and James M. Mulcahy. Copies are available on request: jmulcahy@chicagogsb.edu.

James M. Mulcahy

He writes from Upstate, NY and has over 20 years of banking and 10 years of energy experience. He can be reached at jmulcahy@chicagogsb.edu